Learning to earn vs. learning to learn

Musings on Dewey's democratic, liberal education and the implications of vocational education

Happy Christmas! As 2020 comes closer to an end, we are hopeful, optimistic, and thankful for the support we've received.

Last week, we looked into behaviorism and its influence on Education and Technology. While we acknowledge the practicality of behaviorism, we do not feel particularly excited about a future where education is reduced to the shaping of behaviors.

In a quest to search for an alternate way to educate, we came across John Dewey and his ideology around a more democratic education. What follows in the search is a discussion on the purpose of education and democracy in education. In this article, we'll introduce Dewey and his views on education. Next, we'll discuss a debate that took place between Dewey and Snedden on the future of education and discuss how vocational education crept into liberal education as we see today. Finally, we discuss what vocationalism looks like in 2020 and discuss its implications.

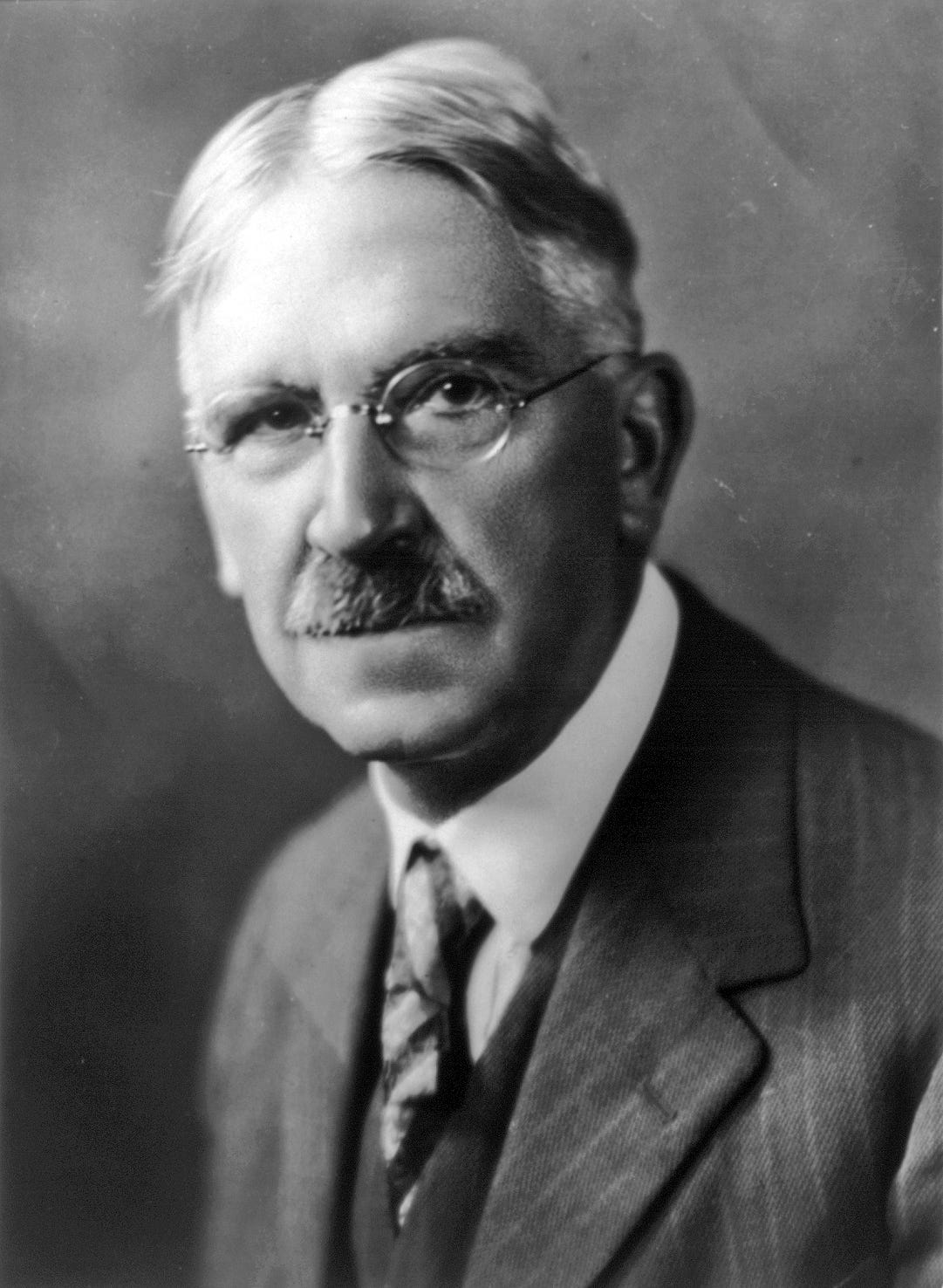

Who is John Dewey and what did he believe in?

John Dewey (1859-1952) is arguably one of the most prominent philosophers and the most significant educational thinkers of his era and, many would argue, the 20th century. As a prominent thinker, he has written extensively on his opinions ranging from art, politics, epistemology, and education.

The next few paragraphs outline some of his beliefs surrounding education and are by no means comprehensive. They are a curated list of ideas that we believe are relevant to better understand the debate that took place between Dewey and Snedden (to be further elaborated later in the article).

Democracy in education

In her analysis, Holt summarized Dewey's view on democracy in the classroom as follows:

John Dewey avidly believed in the role of democracy and the importance of creating classrooms that reflect democratic values so that children would learn to function in the greater democratic society they were expected to be a part of.

According to Ralston, Dewey thought education should:

prepare people for a life of curiosity and inquiry

allow people to grow their knowledge using science and to become more aware of the societal problems

enable people to take initiatives to execute upon problems

In his book, Democracy and education (1916), Dewey pointed out that a democratic society is continually changing—sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse—and it requires citizens who are willing to participate and competent enough to distinguish between the better and the worse. Dewey believed that higher education should uplift learners, liberating their potentiality and empowering them to become ‘masters of their own industrial fate.’

Experiential education

In Democracy and education, Dewey described the main basis of all education as the "reconstruction or reorganization of experience which adds to the meaning of experience and which increases the ability to direct the course of subsequent experiences". As simplified by Hlebowitsh, the "reconstruction or reorganization of experience" is really just a way of saying that one must learn from one's experience in a fashion that avoids repeating mistakes and that contributes to one's ability to make more informed decisions in the future.

For an experience to be educational, Dewey believed that certain parameters had to be met, the most important of which is that the experience has continuity and interaction. Continuity is the idea that experience comes from and leads to other experiences, in essence propelling the person to learn more. He believed that these human life experiences are the contribution to how an individual makes informed decisions on future situations.

The role of a teacher

To Dewey, teachers need to play the role of an effective facilitator in the classroom instead of just lecturing knowledge into students. Additionally, he believed that a student's unique experience affects how they learn and that an effective teacher needs to cater to different teaching methods according to what the student resonates with. He believed that "the profession of the classroom teacher is to produce the intelligence, skill, and character within each student so that the democratic community is composed of citizens who can think, do and act intelligently and morally." In her paper analyzing Dewey's contribution to education, Holt described Dewey's view on an effective teacher:

[A]n effective teacher should possess qualities that promote independence in a democratic society while also remaining knowledgeable about the content area he or she should be an expert in. Additionally, an effective teacher should be open-minded to changes and model good citizenship. He or she should also possess [the] qualities of a good communicator that can collaborate with other professionals to reach the highest of expectations that are possible for students. In addition, the effective teacher must be prepared to think globally about how each student can compete with others for jobs in the future and help to foster growth and use experiential learning to reach personal goals

Learning-to-earn and Learning-to-learn

In a speech titled ‘Learning to Earn,’ Dewey introduced the distinction between the process of learning-to-earn and learning-by-doing. He believed that learning to earn does not build a habit to enable future self-directed-learning that is afforded by learning-to-learn.

As part of his vision for democratic education, Dewey believed that education should do more beyond training students to fill a job. He believed that learning should be deeply personal and students should learn a broad range of subjects to allow them to participate in greater democracy. This was in contrast to the administrative progressive who favored a more pragmatic view on educated: a vocational approach in order to train workers to fuel the economy.

The administrative progressive movement spearheaded by David Snedden led to John Dewey's contribution and ideas to give a distinction between learning-to-earn (vocational) and learning-to-learn (pedagogy). An analysis of the debate between Dewey and Snedden helps us better understand where Dewey is coming from. Additionally, it will help bring clarity on how vocationalism became the foundation of our modern education system.

Snedden vs. Dewey

As documented by Ralston, in July 1914, David Snedden— at the time, the Commissioner of Education for the state of Massachusetts—gave a speech challenging the distinction between liberal and vocational education. In his speech, Snedden argued that "that the old style of liberal education, heavily reliant as it was on custom and ‘mysticism,’ could no longer be defended as higher learning". In his vision, Snedden believes there is a need for two kinds of higher education:

classical liberal education for the elites and

vocational education for the ‘rank and file’

In response to this, Dewey wrote 2 articles to address vocational education. Dewey argued that vocationalists like Snedden erred in two respects:

their vision of vocational education is too closely allied with the interests of industrialists to serve the greater public interest, and

it suggests an imprudent approach to educational reform, whereby no meaningful change is ever forthcoming. Vocationalism merely props up the status quo, a disappointing state of industrial relations warranting the continued exploitation of workers by management.

Who won the debate?

Spoiler alert: not Dewey. It's not immediately clear who won if we use traditional debate metrics such as logic and evidence to judge the debate. However, in the context of education reform, Snedden won the debate if we consider how his idea of social efficiency has made its way into the education system. For example, in 1918 (not long after the debate), the National Education Association Commission issued The Cardinal Principles of Secondary Education and outlined the role of education in a democracy:

The purpose of democracy is so to organize society that each member may develop his personality primarily through activities designed for the well-being of his fellow members and of society as a whole.

Consequently, education in a democracy, both within and without the school, should develop in each individual the knowledge, interests, ideals, habits, and powers whereby he will find his place and use that place to shape both himself and society toward ever nobler ends

Essentially, as Labaree explains in his paper How Dewey Lost, the Commission describes democracy as organizing individuals for the benefit of society, and education as readying individuals to assume their proper place in that society. This is one of the core tenets of Snedden's social efficiency agenda.

So how did Dewey lose?

The administrative progressive message of educational utility and social efficiency had great appeal to policymakers and people in power since it offered an answer to promote economic productivity (vocational education taught students things they could use and apply to the workforce).

The administrative progressives grounded their educational proposals on the authority of science. They developed a way to measure ability and classify students and used these measures to develop curricula and organizational structures and schools. The literature presented in their proposal was filled with scientific terms which helped make the case of their vision as modern and data-driven.

A utilitarian vision is easier to sell politically than a romantic one proposed by Dewey, especially when it comes to expensive publicly-supported institutions like education. While Dewey talked about engaging the interest of the child to promote a richer understanding of the world to promote a more just and richer society, the administrative progressives talked about fixing social problems and expanding the economy.

The education system that took shape was a diluted version of what Snedden proposed (it did not include some of the principles he was adamant about, like the separation of vocational and liberal education). Instead, the administration ran with a social efficiency agenda as an expression of democratic ideals. The changes that took place included: the structure of curriculum tracking, the tailoring of instruction to the academic skills of individual students, the use of standardized testing for student placement, and the shift from purely academic studies to a more practical nature.

Why Snedden's view on education is problematic

Snedden's view of education is problematic because he viewed education as a way to prepare for a person's calling in life. His way of thinking is one that optimizes for social efficiency and is discriminatory: he believed that only the elites should obtain liberal education while the rest of the people should be trained in a vocation.

From the surface, it might look like Snedden's vocationalism is the answer to ending poverty (people acquiring skills necessary to get a higher income job). But critics have argued that it actually does not. Educator and author, Peter Greene, argues that:

[the idea that] education can end poverty as a whole--seems more problematic. Pat leaves the widget assembly line job, which pays minimum wage with no benefits and only provides 29 weeks of work per year. When Pat had the job, Pat was among the working poor. But when Pat leaves the job, the poverty-creating job, is still there and will be filled by someone else, who will still be a member of the working poor. So Pat's life improves, but the total poverty that exists remains the same.

This line of thinking falls into Snedden's view of education and society: people are either consumers or producers. In this model of education, education is a tool to increase their potential earnings and escape poverty; the status quo is always upheld. When someone is educated, another uneducated person slots right into the role.

On the contrary, Dewey's vision of democratic education serves more beyond increasing earning potential. He envisioned that with proper rich education experience, people will be better equipped to cure social ills that need to be addressed including poverty and crime as well as health concerns.

Over the years, elements of vocationalism are integrated into our education system. While it never took over completely, plenty of innovations were made with vocationalism in mind. Let us explore what they look like.

Vocationalism today

The vision Snedden pushed forth manifests today in several ways. Two of the ways we see vocationalism is through vocational schools, and microcredentials.

Vocational schools and coding bootcamps

The first vocational school was established in 1881. However, vocational education began to take off not long after Dewey vs. Snedden, with the passing of the Smith-Hughes Act in 1917 which provided funds to promote vocational education in agriculture, trades and industry, and homemaking. Since the 20th century, we see innovations in the vocational school space.

For example, schools have been utilizing an Income Share Agreement (ISA) as a way to defer student payments. Companies like Lambda School and App Academy make themselves more accessible by allowing students to pay only after they graduate and get a job.

Another pattern we're seeing is companies partnering up with Institutions to either sponsor education or work collaboratively to set a curriculum.

In 2016, Apple launched the first Apple Developer Academy program in Naples, Italy. The program is an exclusive cohort-based program for 2-400 students in collaboration with local universities (with in-person support at the universities) and is free for students.

Since then, the program has expanded to Brazil in 2017 and Indonesia in 2019.

In 2016, Shopify launched Dev Degree, a partnership between Carleton and York University where Shopify pays for the student's university tuition on top of paying students an intern salary. From Carleton University, this is how it works:

Starting right at the beginning of [the] first year, you become a paid employee of our Industrial Partner. The partner also pays for Carleton tuition and fees. Our initial partner is Shopify, an Ottawa-based company that has created one of the world’s leading eCommerce platforms. In the Internship Option, you will take time off work to take your courses in the usual way, attending lectures with other BCS students. Many of the courses taught at Carleton will be supplemented by instruction at the partner in order to integrate academic learning with practical work at the partner. You work alongside industry mentors and gain critical skills to solve real problems with modern technology.

All 3 of the solutions discussed make education more accessible and allows people to break into the industry with less time and/or less money than traditional education. As discussed earlier in this article, Dewey cautioned the problems with vocational education. Additionally, while the programs started by corporations like Apple and Shopify look good from the surface, they do not come without concerns.

As corporations become partners with education providers, a conflict-of-interest emerges. Kenneth Lutchen, dean of the College of Engineering at Boston University, has these to say about Shopify's Dev Degree (and by extension, programs where universities partner with corporations to provide education):

While a tuition-free education along with a part-time salary sounds like a sweet deal for students, Lutchen believes it’s the schools that stand to gain the most, financially speaking. He explains that a significant proportion of students require financial aid, with each one reducing the institution’s overall revenue. When a private company is paying the tab, however, the university is able to collect on the full cost.

“The mission of the institution is not to create employees for a specific company with a narrow set of skills that only that company can use; that would violate the mission of the undergraduate experience,” he says. “In fact, about 40% of engineers end up not working in engineering 10, 15 years after they graduate, so that would be a big concern.”

“The student is made to feel committed to the program rather than have an open mind, because the tuition dollars will stop if they want to switch majors,” he says. “That’s why we would not do that. We would say ‘pay us a certain amount to be on the steering committee, be a member of a consortium of companies.’ And then we know we’re preparing students for a variety of corporate pathways, not just one.”

Microcredentials and universities

Another trend of vocationalism we see today is microcredentials - which are compressed online courses with a highly targeted curriculum to allow the learner to apply the knowledge directly to a workplace.

An interesting phenomenon is a partnership between universities with online providers such as EdX to provide these microcredentials. In his paper, Ralston attributes the rise of universities as microcredential providers to an effort to streamline higher education administration. He details:

The administration of higher education is notoriously inefficient. Registering students. Scheduling classes. Processing transcript requests. Facilitating shared governance. Many of these processes are nearly as labor-intensive as they were 50 years ago.

[One way to address inefficiencies in higher education administration] is servitization. When higher education institutions partner with third-party vendors to provide microcredentials, they effectively convert goods into services. Borrowed from the manufacturing sector, servitization is when a ‘tangible product is replaced or supplemented by an intangible service’ (Arantes 2020). The intentional entanglement of product and service, as well as the ensuing confusion over which is on offer, contributes to a scheme of increased revenue generation (Tauqeer and Bang 2018).

An excellent example is a collaboration between MIT and the non-profit EdX to offer MicroMasters degrees in supply chain management:

The program follows the same curriculum as MIT’s in-person master’s program, except that it covers only about 30% of that material (which is why it is a ‘micro’ degree). That means students take five courses (and pay $1000 in fees) to get the MicroMasters. There is no admissions process, so if a student can do the work, he or she can earn the credential, and for students in the online program who do well enough to gain admission to MIT’s in-person master’s, the online credits transfer, making that degree less expensive. The program recently graduated its first batch of online students, and so far, the supply chain MicroMasters has brought in more than $4 million in revenue, according to Anant Agarwal, CEO of EdX. That money is split between MIT and EdX, which provides the platform and marketing for the courses. (Young 2017b)

On the surface, the movement sounds like a great idea for students: unbundling university courses lowers the price, and removing admission requirements also makes the courses more accessible. However, Ralston offers up a perspective that a conflict of interest between students and corporation might arise by engaging with microcredential production:

As microcredentialing purveyors, colleges and universities also make themselves increasingly subservient to their new clients: businesses and corporations in need of rapid, targeted vocational training for their employees. The traditional mission of enabling student growth through transformative teaching is traded for a corporate mission of maximizing efficiency and profitability at all costs.

As detailed by deLaski:

the boom in microcredentials is being fed in large part by major companies—IBM, Google, and Amazon, to name a few—looking to grow their talent pipeline and increase the skill level of current employees

Furthermore, microcredentials contribute to the decline of the traditional degree by paving a way for people to substitute degree programs. For instance, Kazin and Clerkin ask, ‘[w]hy should an individual bother to pursue a full master’s degree if five courses alone are enough to confer career success?’.

It's important to consider the implication of microcredentials and how it could lead to the Sneddian vision of education where liberal education is reserved for the elite while everyone else goes through vocational education such as microcredential-based education.

Conclusion

I did not understand the intent of liberal education prior to reading Dewey's ideology. I felt that the education system was broken because it taught me a lot of things I could not apply at work. However, Dewey believed that a broad and diverse liberal education will lead to more well-rounded individuals who will then be better able to contribute to a democratic society in order to solve social ills. He believed that an education that is vocational (i.e. an education I can fully apply to the workplace) is an effective way to maintain the status quo and is ineffective for large scale changes:

The kind of vocational education in which I am interested is not one which will ‘adapt’ workers to the existing industrial regime; I am not sufficiently in love with the regime for that. It seems to me that the business of all who would not be educational time-servers is to resist every move in this direction, and to strive for a kind of vocational education which will first alter the existing industrial system, and ultimately transform it].

A large theme towards Dewey's idea of learning-to-learn and Snedden's idea of learning-to-earn, geared towards the purpose of education. When viewed through the lens of job creation and boosting the economy, vocational education does a good job at upholding that. However, in the lens of education and democracy, vocationalism strikes to undermine democracy. In her paper, What Does It Mean to Educate the Whole Child? Noddings commented:

It is not sufficient, and it may actually undermine our democracy, to concentrate on producing people who do well on standardized tests and who define success as getting a well-paid job. Democracy means more than voting and maintaining economic productivity, and life means more than making money and beating others to material goods.

In his paper, Ralston described that microcredentials fall short of educating a whole person. The point he brings up works equally well when we replace microcredentials with vocationalism.

Microcredentialing is unconcerned with educating the whole person. Unlike Liberal Arts education, which catalyzes changes in the entire character of the learner, vocationally oriented microcredentialing seeks only to transfer hard skills and technical competencies to the client-learner. In the absence of a General Education component, microcredentialing tends to cultivate only a single dimension, aspect, or element of the learner’s character, effectively producing a technician, not a well-rounded person. Past president of the University of Chicago, Robert Hutchins (1936/1958), voiced a similar complaint about vocational train- ing: ‘The pursuit of knowledge for its own sake is being rapidly obscured in universities and may soon be extinguished. [ . .] [S]oon everybody in a university will be there for the purpose of being trained for something. [ . .] It is plain, though, that it is bad for the universities to vocationalize them’ (36–7). Insofar as microcredentialing fails to educate the whole person, it exacerbates one symptom of the neoliberal learning economy, namely, the turn away from pursuing knowledge for its own sake and towards learning to earn (Siskin and Warner 2019).

By providing vocational training exclusively, higher education institutions cut their students off from more elevated pursuits (e.g. art, history, cultural studies) and condemn them to a life of subservience to their industrial and corporate masters.

Reading Dewey's work as well as the analysis on vocational education makes us rethink the value of liberal education and vocationalism. The path towards vocationalism is one of least resistance: a solution to help others gain the knowledge for a job sounds like a great thing! However, we need to be mindful of the future we build and take heed of the wisdom from those that came before us.

Thank you for reading! Whether you agree or disagree with what we've written, we love having conversations around Education. So we hope you'll reach out. Drop us a comment below! If you like what we’re doing, subscribe and follow us below.

We'll be taking a break for the coming week and will be back with a new issue in the new calendar year. Until then, farewell 2020, and see you folks next year! 👋